Research Highlight

Unlocking the Secrets of Soil Microbial Metabolites

February 2, 2026

Soil microbes may be tiny, but they play an outsized role in ecosystems. These microscopic powerhouses release small bioactive molecules—“secondary metabolites”—that support nutrient uptake by plants and other critical ecosystem functions. Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) developed a novel method to stimulate and test for redox-active metabolites (RAMs) produced by bacteria isolated from soil at NEON field sites. This research opens the door to a better understanding of how soil microbes support plant growth—and what that could mean for agriculture, ecology and even medicine.

The study was co-authored by David Giacalone, Emilly Schutt and Darcy McRose and published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology: “The phospho-ferrozine assay: A tool to study bacterial redox-active metabolites produced at the plant root.”

Why Secondary Metabolites Rule the World

Darcy McRose

There is a whole invisible ecosystem at work in the soil at the root of a plant. At the heart of this ecosystem is a bustling community of microbes that interact with plants in fascinating and complex ways. These interactions are often mediated by secondary metabolites—small bioactive molecules produced by microbes to communicate, compete and aid in nutrient acquisition. However, studying metabolite production is not always easy. It is hard to detect these small molecules directly in soils. Yet, when microbes are brought into the lab, it can also be difficult to recreate the conditions that stimulate them to make secondary metabolites.

Dr. McRose, an Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at MIT, explains, “A lot of the important interactions between plants and microbes are facilitated chemically by exchanges of these small molecules. We know that the relationship between plants and microbes is very old and very important, but there is a lot we don’t know about exactly what is happening between plants and microbes at the plant root. A big part of that is understanding where different secondary metabolites are found and their function in the environment.”

Dr. Giacalone, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. McRose’s lab and the first author for the study, says, “Soil microbe communities are highly diverse, which means there could be thousands of compounds at work in the soil that we just don’t know about. We wanted to develop a method to identify new compounds and understand where these compounds are found and which bacteria produce them.”

Secondary metabolites are specialized molecules that serve as chemical tools for organisms to adapt to their environment. In the soil, secondary metabolites play vital roles in shaping microbial communities, facilitating nutrient exchange, and defending against pathogens. Their potential importance in the ecosystem is immense—they may be able to unlock nutrients and suppress diseases for plants and even influence the overall health and stability of ecosystems.

Redox-active metabolites (RAMs) are a group of secondary metabolites that facilitate redox reactions, or reactions that involve the transfer of electrons. This ability enables them to participate in chemical reactions that transform and mobilize nutrients in the soil. This process not only supports plant growth but also enhances nutrient cycling within the soil.

For example, phosphorus is a critical nutrient for plant growth and health, but it is often bound to iron oxides in the soil, making it unavailable for uptake by plants and microbes. Under phosphorus-poor conditions, some bacteria produce RAMs called phenazines that reduce iron(III) oxides in the soil to iron(II), releasing free phosphorus in the process. This ability benefits the bacteria and may also help plants that rely on phosphorus for growth.

A New Method for Detecting Redox-Active Metabolites

Despite their critical role in plant-microbe interactions and nutrient cycling, many RAMs have been notoriously difficult to study in laboratory conditions. This is because the genes responsible for secondary metabolite production are often silent or weakly expressed under standard laboratory conditions, making it challenging to detect and analyze these molecules. McRose says, “We know that when some bacteria are stressed for phosphorus, they start making these molecules, but we didn’t know how common this was in the environment. This has been a pretty hard question to ask for methodological reasons.”

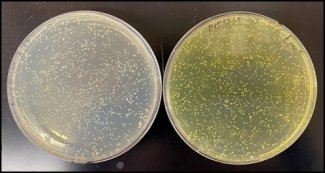

The new screening method uses a phospho-ferrozine assay to detect RAMs involved in iron(III) to iron(II) reduction. Ferrozine turns purple when it reacts with iron(II). Researchers used this property to detect RAM activity from bacterial isolates (individual strains of bacteria isolated from plant roots and the surrounding soil). The isolates were grown in a phosphorus-limited culture medium to stimulate RAM production and then exposed to iron(III). The color-changing assay provided a clear visual signal of which bacterial strains were reducing iron(III) to iron(II). Bacteria that produced a strong ferrozine signal under phosphorus-limited conditions were classified as RAM producers.

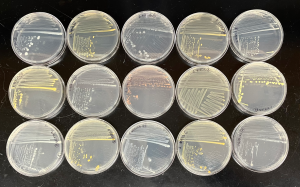

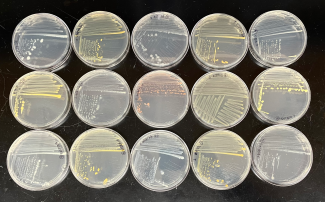

Bacteria cultures isolated from plants' roots.

The researchers tested this method on a library of 557 bacterial isolates derived from root soil samples collected from grasses at three NEON field sites—Harvard Forest (HARV) in Massachusetts, Konza Prairie Biological Station (KONZ) in Kansas, and Santa Rita Experimental Range (SRER) in Arizona—as well as commercial tomato plants. Using the assay, they found that 28% of the isolates produced RAMs in response to phosphorus stress, spanning 19 genera across four bacterial phyla: Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes.

Samples were collected by NEON field staff as part of a NEON Research Support Services (NRSS) project. To preserve the full diversity of the soil microbial community, grasses were pulled up by the roots, packaged along with the surrounding soil, and shipped within 48 hours.

The Biogeography of Secondary Metabolite Production

The phospho-ferrozine assay is a simple and inexpensive method for detecting phosphorus-regulated RAM activity from environmental isolates. This opens the door for future research exploring the biogeography of secondary metabolite production—that is, where bacteria capable of RAM production are found and what conditions support production. Giacalone says, “There is so much diversity in environmental conditions and soil types across the country—some regions are dry, some are moist, some have sandy soils versus clay. I think it’s important to know where these bacteria are making these molecules and the optimal conditions for that.”

The study, while primarily a methods paper, showed that RAM production under phosphorus limitation may be more widespread than previously thought. RAM-producing bacterial strains were found at all three NEON field sites, with nearly 30% of isolates demonstrating a positive ferrozine signal. One unexpected highlight of the study was the identification of a novel RAM produced by Pseudomonas kielensis, a bacterium isolated from the Konza Prairie site. Many soils-dwelling pseudomonads make phenazines, and the researchers expected that P. kielensis might be doing the same thing. However, this metabolite displayed distinct chemical properties and may represent a different type of redox-active compound. Giacalone’s current work is focused on identifying this new compound and the genes that regulate its production.

A better understanding of secondary metabolite production mechanisms could have potential uses for agriculture and beyond. Giacalone says, “Understanding when these bacteria make these compounds and how they do it could be applied in agriculture to help plants take up nutrients more efficiently. There could also be potential biomedical applications for secondary metabolites found in soils, such as new antibiotics to treat infectious diseases.”

Giacalone and McRose hope to eventually build on this study using samples from additional NEON field sites to study geographic variability in RAMs. Data collected concurrently at NEON sites—such as soil chemistry, plant cover and plant productivity—could provide more insights into the interrelationships between soil microbes, plants and environmental variables.

McRose says, “That’s the beauty of NEON. Our work is really focused on the lab, and it’s difficult to have both a robust lab program and a large field campaign. NEON enables us to have this large geographic field footprint with sampling and data collection that is standardized across sites. That means that as we start to see trends, we are better able to contextualize and understand our data.”